Doctors of the cell

Why a family tragedy inspired Dr Mike Champion to pursue a career in inherited metabolic diseases and how metabolic medicine is a rapidly advancing field.

(Disclaimer: these articles discuss themes that may be upsetting to some readers.)

From personal tragedy to professional passion

From personal tragedy to professional passion

When Mike Champion was a young doctor in training, his sister lost a child to cot death. She had put her 11 month old son, Jonathan, to bed one night shortly after Christmas, and discovered he had died the next morning.

“It was just awful,” he said. “When that happens to someone you care for so much.”

No tragedy is more painful than the death of a child. The memory still causes him to well up, though it happened over 25 years ago. But the story has a positive ending.

After Jonathan’s death, a pathologist working on a hunch sent blood samples to a laboratory for testing. The result showed Jonathan had MCADD – a rare disorder of the metabolism with a mortality rate of 25%.

After Jonathan’s death, a pathologist working on a hunch sent blood samples to a laboratory for testing. The result showed Jonathan had MCADD – a rare disorder of the metabolism with a mortality rate of 25%.

Dr Champion’s wife was pregnant at the time and he knew that as MCADD was an inherited disease, their unborn baby was at risk. He arranged for them both to be tested urgently. They were cleared - but others are not so lucky.

Now a consultant in metabolic medicine and head of the Inherited Metabolic Diseases service at Evelina London Children’s Hospital, he explained the danger that children with MCADD face: “When a normal person is fasting, they draw first on the food in their belly, then on the glycogen in their liver, and then on their fat. Fat is full of energy but the brain can’t use it, so the body breaks it down to ketones. The problem for people with MCADD is that they can’t make ketones, so their blood sugar sinks. If you don’t know you have the condition you may not be aware what is happening. Then you develop a coma - or worse.”

A simple solution

A simple solution

Today, families of children diagnosed with the condition can be taught a simple way to manage it – with energy drinks. If the child falls sick and can’t or won’t eat and is therefore enduring a fast, their blood sugar can be easily maintained with a sugar-containing drink. Only if they are so sick that they cannot keep the drink down, then they may need to be admitted to hospital and put on a glucose drip.

“It is a very serious condition but with a very simple remedy. It can be managed easily with the avoidance of fasting. We call it the emergency day regimen,” he said.

There remained a problem however – identifying the children with the condition early enough, before their lives were at risk.

“The average age when children with the disorder first attended hospital used to be 13 months. I was meeting families for the first time in the Intensive Care Unit,” he said.

Screening to prevent tragedy

Screening to prevent tragedy

To avoid more tragedies, a screening service was vital. By the early 2000s, some centres in the US and Australia had already introduced screening for MCADD, but the UK government was cautious. It wanted proof that the condition could be accurately detected and that doing so would make a difference to the outcome.

To supply the proof, the six screening centres for metabolic medicine (in Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol, Sheffield, at Great Ormond Street and Evelina London) joined forces to organise a trial. Half the country was tested for MCADD at birth and the results compared with the other half. They showed that screening saved lives.

“It was the first time I have ever heard a health economist say it’s a no-brainer,” Dr Champion said.

The trial was launched in 2004, and by 2009 screening had spread throughout the country. Since then, not a single child with MCADD has been lost at our hospital.

The successful roll out of the screening programme was marked by an event at the House of Commons – and Dr Champion’s sister was among the invited guests. It was a moment of celebration marked with grief for the family.

“People always say after a tragedy they don’t want others to go through what they did. Now we have achieved that – and they don’t have to. I had wanted this for so long and finally it had come to pass. For my sister to see that there was now a scheme to prevent the terrible thing that happened to her – that was tremendously satisfying.”

Key to the programme was a greatly simplified test for MCADD developed at the WellChild research laboratory, the biochemistry laboratory at Evelina London. The test was known by the scientists behind it as “dilute and shoot” and shared nationally so that all the labs across the country were measuring the same thing to the same level of accuracy. “It showed the NHS at its best, working for the common good,” said Dr Champion.

Disorders of the metabolism

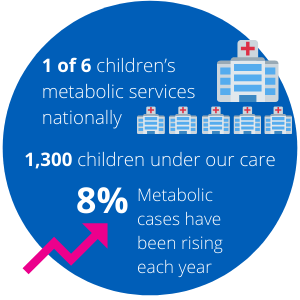

MCADD is just one of scores of disorders of the metabolism - the mechanism by which substances are made or broken down in the body, to produce energy, provide growth and remove waste. They are rare - one in 10,000 children or fewer are affected – but their numbers are growing. At Evelina London, which provides one of only six children’s metabolic services nationally, cases have been growing at 8% a year with 1,300 children currently under the hospital’s care. As medicine advances and diagnostic techniques are refined, more such disorders are being identified each year.

MCADD is just one of scores of disorders of the metabolism - the mechanism by which substances are made or broken down in the body, to produce energy, provide growth and remove waste. They are rare - one in 10,000 children or fewer are affected – but their numbers are growing. At Evelina London, which provides one of only six children’s metabolic services nationally, cases have been growing at 8% a year with 1,300 children currently under the hospital’s care. As medicine advances and diagnostic techniques are refined, more such disorders are being identified each year.

They are a special cause of anxiety because, while rare, they can be rapidly fatal. Yet once diagnosed, the treatment may be as simple as giving the affected child a particular food – or avoiding it.

The first metabolic disease to be screened for at birth was Phenylketonuria (PKU). It is caused by a genetic defect which results in a failure to break down an amino acid and can lead to seizures, behavioural problems and mental disability. Yet it can be simply treated with a low protein diet. The screening test was introduced in 1969/70 as part of the heel prick test, conducted on a spot of blood taken from the baby’s heel a few days after birth. Since then, five more metabolic diseases have been added to the heel prick test.

For years doctors have wanted a more general metabolic screen. When a seriously sick child is brought into hospital the first priority is to discover what is causing the problem, and rule out what is not. But what should they test – the blood? The urine? And which test should they ask for? That is the challenge.

To help them, the WellChild research laboratory has now developed a “Rapid Tandem” screen, by adding more and more conditions and speeding up the analysis so that results are delivered in under an hour. It tells the doctors whether they can feed the child or not, what food or fluids they can give and, in cases where the child is incredibly sick, whether they can treat it. Evelina London will become the first hospital in the country to offer the Rapid Tandem screen routinely.

Not just black and white

However, not all tests yield a clear result. Some are black and white but there is also a “grey tail”, says Dr Champion. “Those children may never have a problem in their lives. Or there may be no effective treatment. Before we screen, we need to be sure about what we are going to do with the result.”

Maple syrup urine disease is one of these – a serious condition which can cause drowsiness, vomiting and coma and is so called because of the sweet smell of the child’s urine or ear wax which can alert doctors to the cause. A recent case was diagnosed in just this way when Dr Helen Mundy noticed the distinctive smell of Harini Rasalingam’s ear wax when she was a newborn baby just seven days old. Harini’s condition had rapidly deteriorated as doctors struggled to understand what was wrong and Dr Mundy’s intervention at Evelina London may have saved her life. Harini spent three weeks in the intensive care unit where she was given life-saving treatment. Now aged two, she continues to receive care from the hospital.

The genetic defect responsible for maple syrup urine disease affects the production of three amino acids (compared with just one in phenylketonuria). But it can be controlled in the same way - with a low protein diet, omitting the three amino acids, but still containing enough protein for growth and repair.

Giving power to parents

Giving power to parents

In the past, affected families were required to attend hospital for regular blood tests. Today, parents can manage the condition at home. They are taught to take a pin prick of blood from their child each week which they send to our laboratory. When the results are available, a dietitian calls to discuss what changes may be required to the child’s diet. “Parents can be anywhere in the world and still effectively manage their child’s condition,” said Dr Champion.

While many specialists focus on a particular part of the body – neurologists on the brain, cardiologists on the heart – specialists in metabolic medicine wander all over the body. It is the specialty where genetics, medicine and biochemistry meet and, as a rapidly advancing field, exciting. “We are,” said Dr Champion, “doctors of the cell.”

The ‘Spotlight on’ features were prepared for Evelina London by, Jeremy Laurance, health writer.

This article has been adapted for use online.